What could be more adversarial – ultimately, more Satanic – than forcing a handful of classic black metal songs into historically queer-friendly electronic music styles? Drew Daniel’s new album as The Soft Pink Truth serves both as a love letter to the sound and spirit of black metal and as a full-on assault of the homophobia, violence, and intolerance that has marked this most feral of musics. But hey, you can still dance to it!

Drew and I carried out this conversation via email while he was on tour in Europe with Matmos. We covered the whole range of typical small-talk, from Shakespeare and Milton to Striborg and Satanic Warmaster; from homophobia and homoeroticism to black metal conservatism and minstrelsy; and from spitting in the eyes of one’s oppressors to bringing Darkthrone to festival-going EDM kids.

—–

Dan Lawrence:

The subtitle of your new album Why Do the Heathen Rage? is “Electronic Profanations of Black Metal.” Based on some of the statements I’ve seen you make elsewhere about the album, I’m wondering if you’re drawing direct inspiration from the work of Giorgio Agamben. In his essay “In Praise of Profanation,” Agamben describes the act of profanation – or profaning – as the act that returns something previously considered sacred back “to the free use of men.” The passage that seems most germane to Why Do the Heathen Rage?, however, argues that “[t]he passage from the sacred to the profane can…come about by means of an entirely inappropriate use…of the sacred: namely, play.”

Is that your goal with this project? To destabilize the “special unavailability” of black metal through play, subversion, and mockery, and thus bring it back to a realm where you can actually do something with it, relatively unhindered by its problematic history of violence, homophobia, extremist politics, and so on?

Drew Daniel:

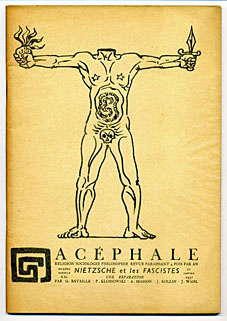

Transgressive acts against the sacred are often locked in a kind of adolescent dependence upon the paternal authority figures that that they defy: you can see this throughout the history of Satanic aesthetics, and you can see it in the thought of Georges Bataille, the photography of Andres Serrano, and you can see it in the t-shirt designs piled up at every merch table at every heavy metal festival. It’s an obvious point: Satanism is a belated and reactionary critique of the sacramental system that it inverts, a rebellious cry of “I don’t wanna” that pushes back against the authority of God the Father. So my project just gives this dynamic one further turn of the screw: now that black metal is its own established canon with respected forefathers, symbols, doctrine and attitudes, what would it mean to Satanically rebel against its authority?

There’s always a tricky dynamic when you are asked why you have done what you have done. If a listener asks “did you mean X when you made Y?” the artist can boost their credibility by saying “yes, definitely”, but it can also become dishonest, a retroactive putting on of airs. While I have taught Giorgio Agamben texts in my life as an academic (especially The Time That Remains, and his book on oaths, which I taught in a course on promises and contracts), it would be dishonest to say that this project draws direct inspiration from Agamben. That throat-clearing out of the way, the quote you provide certainly captures the spirit of what I’m doing: hopefully the record is taken as both humorous and serious, both loving and hateful, and it tackles kvlt authenticity with a stance that mingles worshipful attention to formal details with an oppositional spirit of “Bestial Mockery”, to cite a heavy metal band name. If the “classic” era of black metal has become a set of canonized treasures, then that makes them ripe for a satanic profanation, an inversion of their professed values.

That said, there have been a lot of funny, quick n dirty parodic takes on black metal culture over the years (Vegan Black Metal Chef is just one example among many) and while I can see why this record does undeniably rub spiked shoulders with work like that, it’s not the same thing, in my opinion. There is a novelty music “gag factor” that I cannot deny, and I wear that proudly insofar as I love a lot of music that gets put into that category (Spike Jones, Perrey and Kingsley). But I would also hope that there are dimensions to this record that aren’t so easily resolved, and that don’t let me off the hook by invoking irony as some kind of safe, distancing gesture (i.e. I want to avoid what Derrida termed “the negative certitude of irony”); this record is as much an act of identification with the spirit of black metal, the attitudes and world views of some of its greatest songwriters, as it is a critique of them. In that sense, it has all the crushed out awkwardness of a fan letter.

It’s a playful experiment. I’m asking “what if?” about this music. What happens to these songs when they lose their distortion, their grain and timbre and become simply notes and words? Does their power remain or diminish? I didn’t have an answer in mind, it was a kind of test to see what would happen to a genre if you took away most of its sonic signifiers and reimagined its audience. And I did that with a queer audience in mind.

DL:

Precisely because of the perceived sacredness of black metal, in some ways this project seems like the perfect set-up: What better way to test the self-imposed boundaries of a genre that supposedly prides itself on antagonism, opposition, and iconoclasm? Are you at all concerned about it coming across as little more than a smug fait accompli, though? Meaning, if some listeners get on board with your simultaneously mocking and loving interpretations of the source material, well then that’s great; but if not, and you get knee-jerk rejections of what you’re doing, then it simply proves a broader point that the oppositional attitude of black metal falls apart when directed inward?

DD:

Maybe my masochistic fantasy is that somebody, somewhere will oppress me and denounce this record? Maybe I want those knee jerk responses? It’s a valid question. I certainly got some harsh reactions to my punk and hardcore covers from Crass fans who thought I was committing sacrilege. What would hurt would be for someone to fully grasp my intentions, approve of my politics in a condescending way, but simply hate the record at an immanent sonic level. That would hurt.

More seriously, it seems like the risk here that you indicate is that my record might contribute to an ambient climate of smugness about silly teen sub-cultures which permits those who think they stand with me to adopt some implied stance of adult superiority towards those sub-cultures, a stance that would let both myself and my fans off the hook all too easily, by insisting that we are the upright/good/tolerant ones and black metal fans are the “bad guys”. What could be more self-serving than suggesting that black metal is for uptight homophobes and I’m the fun faggot, so you’d better like my record or be found guilty of being an uptight, fanatical square who “hates fun”? If I recall, didn’t Abruptum t-shirts proudly wave the banner of “NO FUN” as a slogan? (Already familiar from the Stooges and the Pistols.)

Perhaps in making fun of / making “fun” out of black metal, I’m not doing anything radical at all, but simply dragging something beautifully feral back to the land of the cute, and thus back to business-as-usual. In so doing, I would be guilty of pimping myself out as a kind of subcultural variant of the “sassy gay friend” stereotype that is the familiar object of repressive tolerance in a neoliberal media landscape all too keen to celebrate its own ever-expanding comfort zone of acceptance (as long as you make like a good gay clone and consume lavishly, drink the right vodka, etc.). Having taken that critique out for a walk, do I think the shoe fits? Fuck no! Or at least: I would hope not! But it’s not for me as an artist to write my own ticket and prove in advance that this is or is not the case- that’s up to the listener to decide. My motivation in singing misanthropic lyrics and presenting a visual depiction of a murderous gay S&M orgy was to let the project completely immerse itself in the fantasies of hatred and cruelty that sometimes drive black metal lyrics and imagery, and to implicate myself in so doing. If they didn’t appeal to me at some level, there wouldn’t be anything at stake in the project other than a cheap shot at someone else’s credulity.

DL:

To put it a little bit differently: If Agamben’s notion of profaning something so that it can be returned to the realm of actual use, doesn’t the open question then become, what DO you do with black metal once you’ve reclaimed it? Is it a way to make it personally okay for you to listen to the music you enjoy without the twinge of cognitive dissonance? And if so, should we also advocate other musical interventions to destabilize, say, NSBM? I could imagine a klezmer band covering songs by stridently anti-Semitic bands, or someone covering avowedly racist bands in the style of work songs and slave spirituals, for example. (A relevant sidebar, given your Burzum cover that Thrill Jockey posted to coincide with the Pitchfork interview: Did you hear James Fogarty’s cover of “Det Som Engang Var” on last year’s Ewigkeit album? It’s a pretty wild dub/dancehall interpretation of Burzum, and can probably be read with some of the same politics of reclamation that you’re working through here with SPT.)

DD:

I approve of Ewigkeit’s travesty of Burzum, and see it as spiritually akin to what I’d like to think that I have done to Varg’s music. It’s a deliberate forcing of genres into relationships of simultaneous overlap/contamination (saying “see! These things CAN go together!”) AND antagonism/discord (saying “this guy would probably HATE that I have put his notes into this kind of arrangement”). I want the impact of the “both/and” structure to be clear here: genres have richly specific social histories, but they can also be forced into new arrangements and liasons and assemblages and all sorts of combinations that might seem risible or ludicrous or “of questionable taste” are theoretically possible, and exploring that “genre space” is what I like to do, more so certainly than to just add to the pile of existing works in a given genre.

[This is ridiculously general and maybe just goes without saying, but, to take the widest possible view: Music is a socially significant zone in which various individual and collective representatives of various world cultures have participated over time. Their personal statements have then suffered wildly unjust and variable fates as they become exemplary pieces of culture, and get canonized, judged, reviewed, or discarded and forgotten, based on criteria that have more to do with educational structures, prejudices, and the demographics of popular taste than some intrinsic index of quality or worth or what have you. Particularly variable and unjust: the process by which particular works of art compete as commodities in a capitalist marketplace that is itself racist and sexist and prone to reward work that reinforces stereotypes. Genre is thus a place in which the self-vs-society dialectic gets worked out (nothing simple about that!), but it’s also a site of conflict in which shitty, backwards notions about gender and race and class get reified into stereotypes that are used to delimit and separate people, and so we get conditioned to listen to chamber music for “control” and slave songs for “raw emotion”, etc. Obvious enough, but it still needs saying. What this means for me is that there’s a certain obligation when entering into a genre to see it as a dangerous place, fraught with risks that go beyond just the question of “innovation vs. cliché”- ask yourself: whose identities are naturalized and reinforced by a given performance, and at whose expense? Once you’re asking that, you might think differently about how the music you make might act critically upon the scene of the genre to which you’re contributing. Who is this for? Who benefits? ]

DL:

I’m also curious if you feel any resonance with your scholarly interests in Shakespeare. In particular, the central role of mockery and profanation to Why Do the Heathen Rage? got me thinking about the potentially similar role of clowns or fools in Shakespeare. I was thinking about Twelfth Night, but of course, most famously, of the Fool in King Lear. To the extent that fools or jesters were given license to mock or even potentially subvert the authority of the monarch – or at least to speak the truth in ways that other actors were forbidden from doing – do you have any sense of a similar dynamic at work here?

DD:

I see the relevance of the Fool figure in Lear: since the sovereignty of kings was itself a shadow of divine authority and dignity and power, to mock and deride the king was to court blasphemy. But I’m hardly a “court jester” within the black metal scene; I have no influence or position in that world at all. A former graduate student advisee of mine wrote his dissertation on the related-yet-distinct figures of the Cynic and the Fool in Shakespeare (and the place of the Diogenic tradition in Shakespeare generally), and so I am indeed familiar with this component within the Shakespearean archive. (I would also point out that there’s quite a lot that is akin to a black mass in the “Richard II” scene in which he deposes himself as king, since we are witnessing the inversion of a sacred rite of investiture). To be intellectually honest though, it’s really via Milton that my scholarly work as a professor of Renaissance literature intersects with this record. In order to explain that, I’m going to back up and clarify my relationship to religion and to the figure of Satan, since it seems to me that blasphemous gestures and Satanic aesthetics are at the core of this record’s concerns.

I don’t want to mis-represent myself, so let me say: I got off easy, and was never subjected to the truly horrific experiences of many queer youth growing up in the shadow of religion. In a rare moment of candor that punctuated my experience of growing up in the American South, I was informed by a Baptist high school teacher that my Christian mother was going to heaven, but my Jewish stepfather was, alas, condemned to hell. Wandering through a shopping mall in a punk rock t-shirt, an evangelical oddball followed me, approached, and told me with great sincerity that he had looked into my soul and seen that I was a homosexual, and that if I didn’t go back with him to his van for a private prayer session I was assured a place in hell. These experiences, and experiences like them that took place both while I was in the closet and once I was out of it, hardened my sense that being a gay man, no less than being a punk (whatever that meant), meant resisting and overthrowing religious values. Critically neutralizing the power of homophobic, anti-Semitic forms of Christianity was just a basic condition of my own survival in a climate of ambient cultural despair and hatred. It built up a certain reflexive fixation upon acts of blasphemy as a radical queer gestures of revolt against organized religion, which I regarded in a fairly standard punk rock teenage fashion as funny, cool, amusing, maybe even liberating. Christianity was a homophobic oppressor, the faith of Jew-murdering Crusaders, its legacy of violence and ignorance fair game for critique, if not outright mockery and contempt. My first boyfriend was HIV positive, and he later died of AIDS, and the homophobic language of AIDS as a divine plague, so familiar in the mouths of not just the Fred Phelps-es of the world but so many other Christians besides, further embittered me in my sense that the church was first, last, and always, the enemy.

Decades of experience as an academic who studies Renaissance literature have vastly complicated my understanding of what religious faith is, what a church can be, what forms of desire and identity and community can flow in and through religious frameworks, and I find myself now more suspicious of the supposedly secular consensus of modernity than I ever was of organized religion. I’m still an atheist, but I’m by no means someone who uncritically parrots knee-jerk reductionist accounts of religious thought, works, and institutions. And along the way I’ve seen loving and accepting churches, acts of charity and acceptance that complicate my originally rather reductive stance, and I’ve met priests and nuns and believers in all sorts of traditions that have functioned as living counter-examples to the psychic “crash position” against religion that I adopted in my youth.

That said, old teenage habits die hard, and I do still retain a deep fascination with acts of blasphemy and with the aesthetics of Satanism. In part, it’s also a function of my literary training; year after year, I teach Milton’s “Paradise Lost” to both undergraduates and grad students, and that experience forces one to consider and re-consider the Satanic perspective. For me, it’s been a perfect means by which to continually engage in self-criticism as I am forced to unpack these powerfully vivid, eternally opposed religious figures, continually sent back to Scripture and historical sources and theoretical re-considerations in search of new ways to understand Satan and God as Milton understood them. So I intellectually marinate in Calvinist doctrines about “the total depravity of mankind”, theologies of grace, and disputes regarding the nature and extent of Milton’s supposedly heretical departures from standard Anglicanism. This means in particular that I have to think about the nature of creativity itself and how Milton’s text resonantly parallels the divine creation of the world with the open question of how Satan might or might not bring something truly “new” into the world: the birth of Sin from his forehead, the erection of Pandemonium in Hell, or, most catastrophically, his temptation of Eve and precipitation of the Fall itself. What is Satanic creativity? The capacity to destroy, pervert and ruin what others enjoy.

All of this personal history is relevant to the question of why I would make this record. Quite simply, and at the risk of repeating myself to you, let me say again that I love black metal and hate black metal. I love its intensity, I love its riffs, I love its capacity to channel extreme feelings of hatred and anger, to let loose with vicious, unrelenting force dark energies of negativity, I love its weird monotonous insistence upon very basic patterns and very simple emotions, its minimalism in all senses. I love its formal and emotional stuckness, precisely because it has a curiously liberatory effect upon the mind. I have spent hours and hours of my life reading and writing as blastbeats puttered steadily, endlessly onwards, offering a kind of weirdly soothing motorboat-like putt-putting noise in the room upon which my thoughts and feelings can ride. That said, some of the “best” records in the genre have been crafted by murderous, homophobic, Anti-Semitic racists, by people who burn churches, by people who kill their friends, by people who kill random gay men whom they target because they are gay, by people who spread virulent, toxic stupidity. So I have good reasons to hate black metal. I have good reasons as a gay man to feel specifically threatened and targeted by the components of black metal fandom that glamorize these crimes, and, gay or not, the criminal track record alongside the ideological disaster area would seem together to offer sufficient reasons simply as a human being to be disgusted by black metal fandom as such. The conundrum of loving black metal for its aesthetic rewards and hating black metal for its political demerits is a fairly typical situation, and probably one I share with plenty of other people. But I do love the music, even as I feel deeply uncomfortable with the people who make it and many of the other people who love it. That ambivalence is why I made this record.

In crafting covers of black metal, a subculture which is explicitly Satanic in its lyrical themes and images, the question for me was: how could I take a Satanic stance towards something that is already itself Satanic? The answer: ruin it, pervert it, turn it against its intended use, take something that is fun for people and push it towards its opposite. Take away their precious plaything and fuck it up. Dance music is a complicated form, made by lots of different kinds of people and used to express lots of different emotions. But there is a sense in which the shorthand functionality of dance music is explicitly tied to pleasure and collective celebration: that’s what dancing is, or can be—as Theo Parrish’s song title puts it, “Heal Yourself and Move”. With this record I’m taking black metal, a form explicitly about Satanism, hatred, sorrow and grimness, and turning it into shiny, bouncy, upbeat dance music- while retaining all of its lyrics and riffs intact- so that it’s undeniably black metal and yet also just as undeniably perverted against its emotional and stylistic grain into becoming something else, something historically associated with gays, with black people, with girls, with fun and sex and joy and release- i.e. with everything that black metal, neurotically trapped in its inhuman impasse of Nordic landscapes of pristine white snow and its pristine white corpse-painted faces tries to disavow or crop out of the frame. That very contrast between song as lyrical/musical template and kind of electronic pop music execution struck me as the most “Satanic” thing you could do to black metal. And in that sense I am trying to be both “true” to black metal’s values (I am being a Satanic adversary) while being also, as “false” as I can possibly be (I am being the dreaded artsy faggot who plays fluffy, inconsequential games with Serious Man Things). This is a genre obsessed, in some cases literally to the death, with authenticity, and my desire is to ruin that in as many ways as possible, while still revealing an entirely earnest formal engagement with what remain, for me, a bunch of great fucking songs.

DL:

Maybe this isn’t the case if you had an explicitly queer audience in mind when writing/arranging these songs, but in some of your last comments there, I wonder if you aren’t leaning pretty hard on the notion that electronic music in general is coded or interpreted as almost innately queer-friendly terrain. I understand your broader point about the history of dance music being associated with a variety of disadvantaged or marginalized social groups, but for the most part, it’s not like you’ve turned these black metal songs into, I don’t know, pure disco or Hi-NRG or something. In fact, there are plenty of moments throughout the album that could pretty easily find themselves in the harder-edged stable of experimental labels like Hymen or Ad Noiseam.

So I guess maybe that’s a roundabout way of saying, I wonder if in highlighting the way that queer-coded dance music might pervert and profane black metal you could be overlooking some interesting similarities. In particular, one point of consonance between these otherwise disparate musical genres seems to me to be the notion that they both are intended to induce a surrender of sorts. Of course, most paradigmatically, you have Venom’s genre-founding chorus: “Lay down your soul to the gods’ rock and roll.” But even just in this selection you’ve chosen, you’ve also got the sentiment of Sargeist’s “Satanic Black Devotion” (which, incidentally, might be my favorite cover of the bunch – I really love the Velvet Underground-styled opening). With dance music intended for clubs, there’s also a powerful bodily effect. In essence, at their most primal, both genres seem designed to induce the listener to giver herself up to – or at least over to – some irresistible thrall.

DD:

Yes, there’s a sense in which the sublimity of surrender on the dancefloor and the sublimity of surrender in the moshpit are two paths to the same goal, which is a kind of ego death and collective merger. You can turn off your mind and become overwhelmed by giant sub-bass or you can turn off and your mind and become overwhelmed by the sheer volume of giant Marshall stacks. In either case, there’s a physiological dimension of submission to vibrational force that doesn’t entail all this elaborate cultural coding and gendering of this genre versus that genre, though dance music and doom metal tend to go with low end while black metal insists upon a shrill high mid-range sheet of sound that is arguably closer to Coltrane. I’m glad you like the Sargeist cover, if I can be honest and say something that might sound gross it’s my favorite song on the record too: I wanted to cover a song about fanaticism, about being a “fan” of something in the deepest sense, and it’s the song that pushes me the furthest into uncomfortable genre territory, insofar as the contrasts between clean singing and screeching/screaming verges on the “crabcore” genre of Attack Attack and Brokencyde, a truly abject and deeply uncool genre- which is precisely why it was interesting to me. Having to belt out those words tested me, because I’m not delivering it in a campy, “ironic” voice- I’m trying to go for it, as honestly as I can.

DL:

One thing about black metal – which, if I haven’t yet made clear, I also have an abiding love for and troubled relationship with, although as a straight white man, the threat that black metal poses to me is primarily a threat to my own self-image as a progressive leftist sort of person – that has always seemed so maddening, even outside of the violence, stupidity, hatred, and backwards politics, is that for a music which presents itself as something to be taken extremely seriously, it is almost singularly hostile to attempts to engage with it in an intellectually serious manner. Of course, as the genre with perhaps the most heavily stylized aesthetic and most ritualized presentation, there’s a serious dose of performativity to reckon with. (It has, for the record, taken a not inconsiderable amount of self-control to avoid going crazy with punning on Judith Butler via Genre Trouble…) Do you think that’s all just due to the coagulation of certain default modes of presentation? I mean, you don’t see many death metal bands putting on airs of having read loads of Nietzsche as a prerequisite for making music in the appropriate spirit.

DD:

I took part in the second Black Metal Theory Symposium event at the Fighting Cocks pub in Kingston, UK, along with Scott Wilson and Ben Woodard and Nicola Masciandaro and Evan Calder Williams and Eugene Thacker and many others, so I’m definitely already “guilty as charged” when it comes to the tricky prospect of theorizing about the implications, assumptions, and aesthetics of black metal. Doing that triggers hatred and disdain. If I recall correctly, the first Symposium immediately triggered online comments of the “Drink shit, falsers” variety. I would be disappointed if the conjunction of black metal and theory didn’t trigger skepticism and resistance and hatred, as those stances and affects are hard-wired into this subculture. [Predictably enough, that kind of denunciation of my album as false / weak / etc. is already going on on various metal message boards as we speak.] The irony is that much of the theorizing of black metal is itself bound up with the articulation of various kinds of cosmic or ontological negativities (scenarios of planetary extinction, metaphysical meditations on non-being and the void, ecological evocations of dead environments) which are, themselves, mimetic of the positions, zones, or concerns felt to be already present within black metal aesthetics. Stepping back, you can see that there’s a sort of mirror logic in place between the negativity of those who hate the theorization of black metal and the negativity of the theories themselves, and a kind of “race for the bottom” ensues: who can think the darkest thought? Who can hate the most intensely? Who can limn the most utterly final scenario of loss and nothingness? Who can evoke the bitterest curse? My own contribution was to bring up race and to ask about how we might understand corpsepaint in the context of the long history of onstage minstrelsy- even if in this case there’s a kind of cross-identification with the dead rather than a cross-identification across racial barriers. The image of the black metal kvltist as a deathly pallid, militant/morbid icon raises the question of the historicity of black metal aesthetics: it’s a kind of anachronistic free for all in which ancient pagan warriors and medieval Vikings and early modern melancholics and malcontents and German Romantic wanderers and nineteenth century diabolists keep blurring and melting into each other. The pallor of the corpsepainted face revises the Renaissance cult of black bile (in which the face was darkened by bile) into a pallor closer to the Romantic cult of tubercular beauty, a whiteness that is implicitly racialized. At any rate, my essay on this topic is forthcoming, so consider this a kind of “teaser” for that piece.

DL:

I also wonder what you think about the potential homoeroticism of black metal. It’s certainly not played-up as intentionally as you might find with industrial music, for example (whether Laibach covering Queen as part of their subversive totalitarian spectacle, or, well, pretty much anything by D.A.F.), but your choice of songs – as you mentioned in your interview with Brandon at Pitchfork – seems to play up the often underplayed sexual element of black metal. Your cover of Venom’s “Black Metal” takes obvious joy in highlighting the line “Riding Hell’s stallions, bareback and free,” for example. Are you intentionally reading more of that content into the music as a pointed way of profaning the intolerance of the genre, or do you think there’s more genuine homoerotic content than is typically recognized?

DD:

The smoking gun here might be Euronymous’ infamous/alleged remarks that “anal sex is more evil than vaginal penetration”- a symptomatic and not-un-hilarious position to take. What’s interesting to me is not speculation about particular people and their identities but about black metal as a deeply artificial stance in which the reactionary adoption of something as “evil” counts first, and the actual sexual act comes second- that, to me, is far queerer than any normative identity, homo or hetero. That is what is queer about black metal. Indeed, one could align quite a lot of the virulent “anti-life” positions and stances adopted by black metal musicians with the recent positions taken in the so-called anti-relational wing of queer theory (I’m thinking here of Leo Bersani and Lee Edelman). Edelman’s position in “No Future” is that queers, because they do not (generally) reproduce, become the cultural bearers of the death drive. Insofar as all political rhetoric is bottle-necked through the future and the image of the child as that for which we must strive, work, and produce, the doctrine of “reproductive futurism” binds creating children and believing in life and the future together. Against this normative backdrop, queers refuse the future and refuse life. (You can see the curious sense in which this very positions risks reifying the worst aspects of anti-gay rhetoric, but that’s not what Edelman is up to). As I see it, the black metal kvltist posturing against life indicated in countless album titles, song titles, and t-shirt designs (“Massive Conspiracy Against All Life”, etc.) as well as in the practice of corpse-painting the body until it looks dead comes to occupy precisely this position: embodying the death drive, refusing the future, refusing to accept life as a positive value. In this particular sense, black metal as a culture is already queerer than queer. As such, it doesn’t need me to show up and make jokes about how gay it is, or how homoerotic it is (though of course when you go see Enslaved and the guitarist dude’s abs are on display to a room full of sweaty, nervous-looking men then there’s a completely obvious dimension in which that is what is going on). But bracketing that, black metal is already queerer-than-queer because of its insistence upon artificiality (make up, posturing, highly aestheticized rituals) and its hostility to “life” as a value. That’s part of what fascinates me about it- its cold, ruthless intensity.

DL:

To take a bit of a detour: How has the tour been going? Is it a joint Matmos/Soft Pink Truth run, or are you just playing solo the whole time? I’m curious, in particular, how any of this new material you might be playing has been going over. Are people dancing? Laughing? Shifting uncomfortably in place?

DD:

It’s a Matmos tour, and we’re playing almost entirely new material based on M.C. Schmidt’s video pieces; we’ve brought our friend Jeff Carey from Baltimore to start each night, and he plays very loud harsh power electronics with an array of 50 joystick-controlled strobe lights, so it’s a heavy night. I’ve been doing some strategic Soft Pink Truth strikes in various cities, and while I can’t be objective, in my opinion they’ve been a blast, and surprisingly effective, since I was girding my loins for a wipeout. In London, I did an afterparty gig at a queer R&B night called Vogue Fabrics in Dalston: a tiny, sweaty basement full of stylish young gay dudes that are into weird remixes of Rihanna and Beyonce. My stuff is definitely not wanted in that environment, but I went into “frontman” mode and got them throwing the horns. People were into it, I was a sweaty disgusting mess, fun was had.

A few days later, I was booked onto one of the three main stages at Distortion Festival, which is a huge free techno street party in Copenhagen- it’s like 50,000 people wandering around drunk and yelling and getting down to huge, blown-out bass heavy soundsystems all through the city, it just takes over. Tons of blonde Danish jock-bros and Euro babes in sunglasses with expensive purses staggering around. I was on immediately after DJs playing Lil Jon and Chingy and big “festival trap” EDM anthems, and I was kind of shitting myself, thinking “these people are going to fucking hate me”: there was a crowd in front of the stage of thousands and thousands of people who do not give a single fuck who I am or what I’m doing. They were laughing and looking confused when I launched into “Black Metal”, but by the Darkthrone cover, I had a mosh pit going and I was laughing my ass off because, seriously, I never expected that kind of reaction. I think young, drunk people want to go off, you just have to hit them with the right tempo and the right forceful structure and it can happen, even for something as prima facie implausible as what I’m putting out there.

The following night, I played an afterparty in Berlin thrown by Ex-Berliner magazine at a space called FluxBau, and it was a very fashion-goth kinda scene, people had dressed up and it was pretty insider-ish, I suppose. But again, if you just grab the mic and walk right out into the crowd and sing directly into people’s faces, they look offended and surprised at first but then they get into it. By the Hellhammer cover, somebody was crowd-surfing, and it was a low-ceilinged bar, so their face was kinda right up to the ceiling. When I did the Mayhem cover and screamed the line “Feel my body’s steeeeeench”, I walked into the crowd and held my armpit out and people in the crowd were pressing their faces in to sniff my armpit. I consider that success.

(It sounds gross or like bragging so I don’t really wanna do that, but you asked.) So the lesson here is that this stuff can work live (though maybe I just got lucky or standards were low when people are really drunk and it’s 2:30 am). At any rate, what I’ve learned is that it’s very hard to mix the modes of “frontman” and “live electronic jamming”- if you’re on the mic and directly delivering the song to people, they’re down, but you can’t do that and then walk over to your laptop and just fuck with the beats in a standard live laptop performance manner, because they will lose interest. You have to present these songs with conviction, you can’t approach it in a tongue-in-cheek manner or it falls apart. So the risk here, it seems, is becoming a rock n roll ham. So that’s a new problem for me to deal with.

DL:

Another tangential sidebar: How do you see the relationship between your music in Soft Pink Truth (but with this new album in particular) and what you set out to do with The Rose has Teeth in the Mouth of the Beast? (An album which, in the interest of full disclosure, I love, although my favorite Matmos album might be The Civil War. Oddly enough, I have this weird association between The Civil War and Iced Earth’s The Glorious Burden, in part because of the similar subject matter, and in part because they came out around the same time. The Iced Earth album is also mostly a shitshow, but that’s a separate issue. I also make a weird mental connection between A Chance to Cut… and Fantomas’s Delirium Cordia, so go figure.)

DD:

The Soft Pink Truth is about my own discomfort with dance music, my shame and embarrassment at slipping into gay clichés: the business-as-usual expectation that gay people make and like house music. That’s a source of shame to me as a hardcore kid, because I feel like that reductive stereotype was part of what kept me in the closet when I was in highschool- feeling like I related more to Black Flag than Erasure, not wanting people to assume that I liked “weak” music. But I got over that. I went to college, stopped being straight edge, started taking LSD and going to raves, and decided that dance music was nothing to be ashamed of and was, in fact, kind of amazing when done well. (Stop the presses! College kid takes drugs, dances!) That said, though the Bay Area early 90s club scene I entered was incredibly fun and anarchic and amazing, full of vital and freakish people, it was also ravaged by drug addiction and AIDS, and so partying was always shot through with desperate reality-checks that I saw first hand: my boyfriend was a party promoter who threw illegal raves and had a meth problem; he died of AIDS while I was in college.

Following from that, The Soft Pink Truth is also about failure, about trying so hard to party that you fall apart: literally, the name comes from a remark made by the doorman of a gay bar about a local DJ and drug dealer who was nicknamed “Soft Pink Missy” because he took so much crystal meth that he could never get a hard-on. SPT has humor and a kind of subtle sadness in the way it handles dance music because it acknowledges the limits of the utopian slogans that circulate in dance music. I understand their appeal but I also see their horizons and edges. So it flags a perverse relationship to dance music and the genre/sexuality linkage as such, and the particular queer culture that crystallizes (not to pun) around that. “The Rose Has Teeth In the Mouth of A Beast” is an album of queer historiography, it’s us imagining a series of biographical incidents as audio-portraits of queer ancestors, I think it’s more respectful and also more melancholic: so many of our subjects descended into madness, alcoholism or suicide, so there’s a kind of tragic undertow to the album that references some of the same issues that are also in the background of SPT’s name: pleasure and its obverse.

At the end of the day though, SPT tracks are meant to be fun and functional, they need to make people (at least potentially) dance, or they aren’t doing their job. Matmos make no such promises, we try to bring a certain playful spirit to whatever we do, but we are also free to get dark and unsettling, either at the level of sound source or the level of form. The projects are siblings, but Matmos is more grown up, and, I hope, more ambitious.

DL:

I’m not very well-versed in recent queer theory, and theory descended from Lacanian psychoanalysis is something I mostly managed to avoid throughout grad school, so I don’t know much about Edelman. It seems that to make the case that there’s real congruity between a politically liberatory queer denial of futurity and black metal’s anti-life/anti-future philosophy, you’d have to believe that black metal’s hostility to life is somehow similarly politically oriented, or at least that it arises from some deep philosophical motivation. Of course an artist’s text can always be read in ways other than she intended, but for me, it’s hard to see the vast majority of that anti-life sentiment in black metal in any other light than simply a default, reflexive expectation of the genre’s aesthetic. (Not that punk automatically gets a pass because of its explicitly political context, but “God Save the Queen”‘s “No future” just feels a bit more believable than Dissection’s anti-cosmic talk, or the hermetic isolation of Striborg or Beatrik.)

DD:

You’ve put your finger on a basic methodological question: what politics follow from the death drive? The typical answer would be a conservative politics: if we assume that there is something self-destructive and aggressive in people, then we firm up the law to protect each of us from this very negativity. But is that the only outcome? What other relationships to negativity are possible? Black metal’s embrace of the death drive (its repetitive formal monotony, its lyrical stances of warlike hatred or depressive despair, its open celebration of murder and suicide and arson and war) can be modulated into rebellious or authoritarian political directions. Satan, too, as a figure who is both a rebel against God’s authority and a kind of “king of hell”/monarch figure also embodies this ambiguity. So the question is: if heavy metal as a genre is so obsessed with fantasies of power, what follows from that? How does identification work here? Are we identifying with victims or perpetrators, or both? Heavy metal isn’t simple because people aren’t simple.

DL:

To circle back a little to the question of your own personally fraught relationship with black metal: I can imagine a response to your political project in this album being, “Okay, for a variety of reasons, you’re opposed to the actions of some of black metal’s most notorious musicians, and to the intolerant attitudes and behaviors that many musicians and fans may hold. So why not just listen to black metal from bands/musicians that haven’t been implicated in the violence of the early ’90s, or in the reactionary politics of a lot of fringe, underground black metal?” Basically, why not just avoid Burzum, Emperor, Dissection, Mayhem, anything out of Blazebirth Hall, and anyone else with clear, documented connections to violence and politics you find hateful? Here’s the real thrust of my question: By selecting songs from artists like Venom and Hellhammer who – at least to my amateur historian’s knowledge – have not engaged in violence or dodgy politics and then linking them to your project of intentional, political profanation, don’t you risk totalizing black metal into something morally reprehensible by nature rather than by choice of an individual band or artist? Or do you think that in some ways the whole genre is guilty by association?

I suppose I’m just thinking of the variously intellectually dishonest and disingenuous ways that fans of this music rationalize their musical preferences. I’m horrifically guilty of this myself, by – for example – finding it easy to disregard Varg entirely these days because all of his post-prison albums have been dull as shit, or by having a couple Nokturnal Mortum albums, but hey, they’re on cassette!, so… I guess that makes me feel like I’m not supporting the band in a meaningful way? It’s a nonsensical thought, but most of the time I can get by without dwelling on that too much. I guess maybe that’s a circuitous way of saying that I hope your album causes people to think more closely through some of the moral compromises they may have found ways of disregarding or explaining away.

DD:

Yes, the “some are / some aren’t” distinction is an important one to make, and it is useful because it deflates the hysterical, tabloid reaction to this genre that sees no difference between genuinely NSBM and other black metal bands, who have many different political affiliations, or no discernible political affiliations at all. I have mixed this album up because it’s meant to be a portrait of black metal across time and across topics/styles, so there’s a range of bands from Brazil to Finland and there’s a range of bands historically from prototypes like Venom to late-comers like An. I am trying to construct a kind of “family portrait” of black metal as an aesthetic tendency, and by necessity that means I am going to be lumping together groups which don’t see eye to eye. My profanation is a profanation of the genre as such, not just an attack on “bad guys” who somehow deserve it because of their politics: I’m lovingly assaulting the entire genre. But how could any selection be representative or fair when you’re talking about a huge range of different people? In the case of Darkthrone, you’re also talking about a classic band that has evolved and changed styles and matured in public, and no one song is going to sum them up. Given the diversity of their back-catalogue, how could it? Though the sequence of covers emerged in a piecemeal fashion, I designed the album to be a companion to my last album of punk and hardcore covers, “Do you Want New Wave or Do you Want the Soft Pink Truth?”. And on that album, I had covered “Homo-Sexual”, a homophobic song by The Angry Samoans that I loved as a teenage closet case. In the case of that cover, it was about acknowledging the harm and damage done by sub-cultures to minorities.

That said, on this record I didn’t cover Satanic Warmaster or Peste Noire. I just didn’t feel that I could successfully flip their songs in the way that I felt that I could flip the Samoans. It was a judgment call. In the case of this album, it’s less straightforward. It’s about the murk and ambiguity surrounding how songs operate as fantasy spaces in which multiple constructions are possible: one person’s anthem of hate might make some other listener feel powerful, feel understood, feel like they were part of some community. Songs aren’t simple. When Darkthrone sing the phrase “the burning slaves”, is that a racist line? Is that a racist image? It can be given that construction, but in the context of church burnings it might have other meanings: slaves of God, slaves of Christ, who are burned in a pagan uprising against Christianity. It also might mean one thing to someone from Norway and mean something very different to me as a listener: I come from Kentucky, from a segregated childhood in the American South, from the land of the Klan. My ancestors in Alabama owned slaves. I am a white descendent of that Confederate history, so a line about “burning slaves” encodes, for me, a horrific American past that may have absolutely no resonance or relevance for the Norwegian author of the song. But in covering the song, I’m trying to work through the politics of black metal as a subculture in which things migrate across context and change, gaining and losing power in the process. I’m part of that change, a perverse twist in the circulation of this music, giving it a spin of my own, taking these riffs and notes and words and relocating them.

DL:

In naming the album Why Do the Heathen Rage?, were you mostly focused on the biblical reference (to the second Psalm), or on Flannery O’Connor’s story of the same name? Both? Neither? And – crucially important – did you not consider naming your album of dance music transgressions Why Do the Heathen Rave?

DD:

To answer your final query, it was the Psalms that I had in mind, and honestly I worried that the Flannery O’Connor use of the phrase might be a distraction. But it felt right to me as the third-SPT-album-title-as-question gesture in a row, and it posed a core set of questions for me and for the scene: what is the hatred at the heart of this genre about? what is it directed at, and what does it mean? what are these kids so angry about? why do I, as a middle-aged academic, gravitate to this stuff? What’s the emotional core here? The pun you’ve proposed is excellent and apt, but I worried that it would cement a purely humorous construction of the album, and I wanted it to be a bit more open-ended and possibly serious, in part to balance out the provocation of the artwork. But perhaps I should have gone for it?

—–

Many thanks to Drew for being so generous with his time in carrying out this interview. Thanks also to Invisible Oranges‘s head honcho Ian Chainey for allowing us to publish this full, unedited interview here (an abbreviated version of the interview appears today at IO).